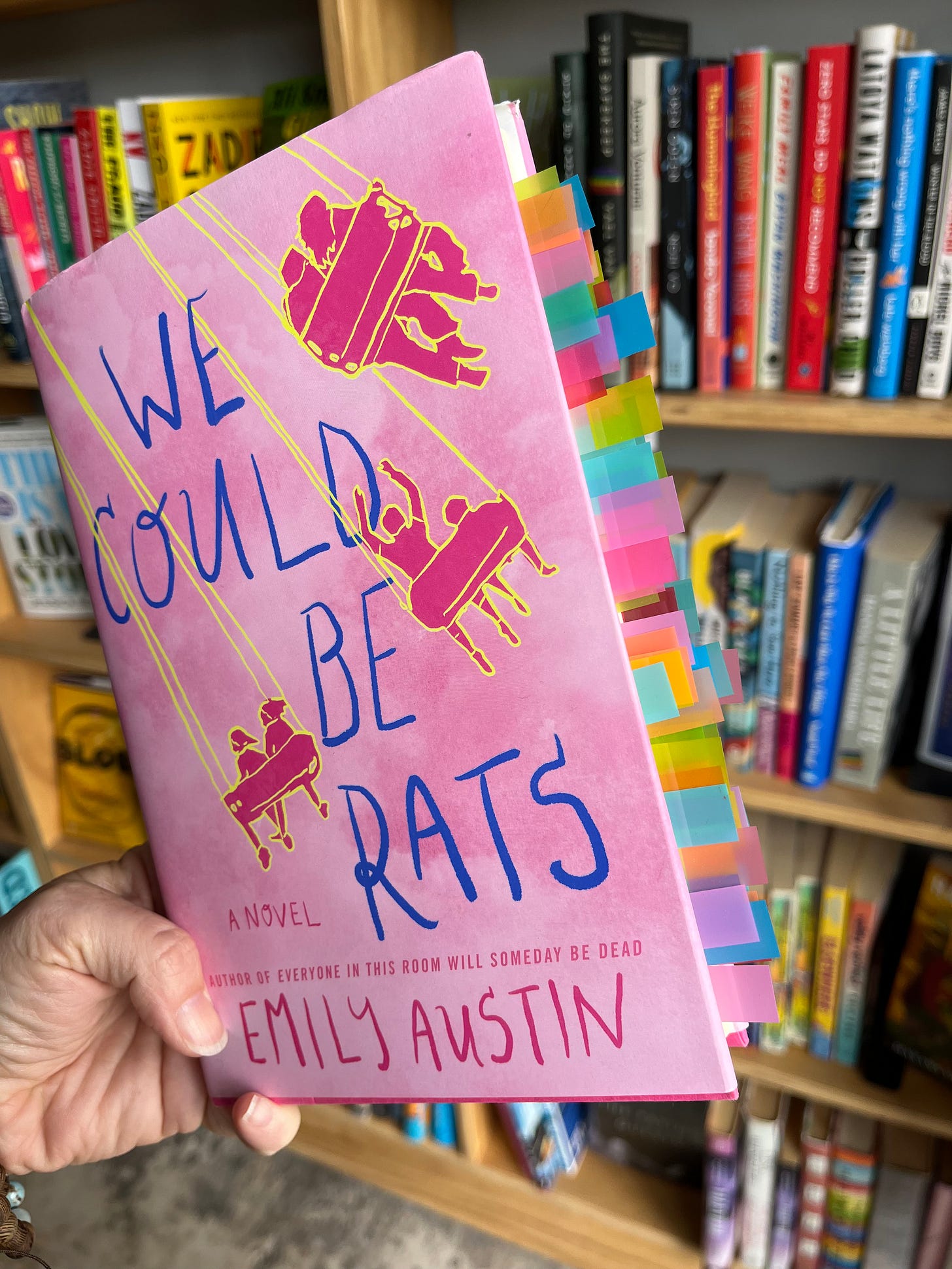

Bookish Community Book Club: We Could Be Rats

This month: more book interaction, less book review. Come share your thoughts with the group! Really. It'll be good fun.

I liked We Could Be Rats so much it's stupid.

I can’t even be reasonable about this book. I love it forever. The End.

Except I suppose that doesn’t really make room for good discussion.

I’m facing a conundrum, as you can see.

So, this time, the format for our Bookish Community Book Club discussion is going to be (a whole lot) different. Here’s how: I am going to pick one thing I liked about We Could Be Rats, and I’m going to write about that one thing. Think not a book review but a post about one of the ways Emily Austin made me fall in love with her book.

Then it’s your turn.

Either pick something you loved (or hated… I’m trying to leave room for our differences here, y’all) and write about that one thing. You can be as personal as you’d like. Or you can maintain a level of distance & decorum. Up to you.

Leave your post in the comments. Feel free to respond to each other’s comments. Let’s see if we can get a discussion going. I’d really, really love that.

I’ll go first.

I’ve never identified with two characters—simultaneously! But Margit and Sigrid both spoke to such distinct parts of me: the older sister who tries so hard to be buttoned up, to keep everything in order, to smooth ruffled feathers, the one who goes along to get along. The one who is dying inside.

And the younger sister who is, in her family’s estimation, a fuck-up of epic proportions. She’s gay (gasp!), a vegetarian, has very distinct ideas about her family’s bigotry, racism, and conspiracy theories, and just doesn’t fit in. The outcast.

I am both.

In the beginning (when all those draft submissions of Sigrid’s suicide note were coming through), I was falling in love with Sigrid’s tender, down-to-earth view of the world. Like her slightly depressive pontifications on ordinary-ness:

“I am not sure why we tell kids everyone’s so unique. We aren’t really. I get wanting to make kids feel special, but most people are more of the same. It might be easier to grow up if kids weren’t sold this tall tale that we’re all exceptional. It might make it less jarring to become an adult if we knew the truth the whole time. We’re mostly ordinary.

Do you think of this kind of thing when you think of snow? Do stories containing snowflakes make you feel dull and average?”

I wondered, immediately, how Emily Austin had gotten into my head. How she knew that in my 20s I absolutely believed growing up was a sham—some lie we were sold to make us all fall in line. But I also had this tremendous sympathy for Sigrid (I mean, yeah, I know she’s not real—but for all the hearts out there feeling all dull and average). Because I’ve settled into my ordinariness. Or I’ve found my uniqueness. Or maybe I’ve stopped worrying about either and just leaned fully into being myself.

But also, just a page later, when Sigrid says:

“All I’m trying to get at is that I have felt enormously happy. I cackled around town, drank myself gay, loved a doll, and watched snow plummet from the sky. I can’t imagine anyone has felt happiness more profoundly than me. I got to the peak. I don’t intend to kill myself because I am unhappy. This has nothing to do with that.”

I just couldn’t.

Because as a person with all the big emotions, I have felt elation and despair within 24 hours, just because the wind blew sideways. Being intensely sad, or let down, or depressed doesn’t mean that you haven’t felt elation, you know?

It’s just this essence of being human, this grittiness, I felt like Sigrid was getting down to. Except this wasn’t Sigrid writing at all. It was Margit. Trying desperately to write the suicide note that Sigrid had asked her to, trying to figure out how she ended up sitting in a hospital room waiting for her sister to wake up—and beginning to understand that she might not.

I get that too—the dazed, befuddledness of staring at a situation, knowing it should be just a normal Tuesday and not being able to figure out how you got from normal to this fresh hell.

I think we all have flavors of that in our lives, right? I don’t know. But I have. And seeing my own thoughts on the page felt wild, like being seen by the Universe in some way.

Oh, and then when Sigrid (but really still Margit writing as Sigrid) goes on to talk about the ways that her family doesn’t know her, the ways they find her difficult, act as if everything she does is an affront to them. I’m not going to say that didn’t feel shockingly familiar, too. This is when I started chasing my family members around the house, reading sections of We Could Be Rats to them. Attempt Five of the suicide note, when Sigrid (really Margit) breaks down their dysfunctional family dynamic for their parents, is stellar:

“I wasn’t a difficult person around other people. In fact, I didn't think anyone outside our family would describe me as exhausting or dramatic. I think you might have a warped perception of me. People saw me differently than you saw me. I saw myself differently than you saw me.”

Same, girl. Same.

I know plenty of people have jacked up family dynamics. But I swear on all the deities, Emily Austen could have pulled that right out of my journal.

I just want to say it loud and clear: representation matters. The misunderstood lesbian in a homophobic, religious family? If I’d had access to these characters when I was 19 years old, they might have saved me from years of agony. And no, I am not being dramatic.

And then.

Then Margit told THE TRUTH. And that twist broke my heart (but damn that was a clever and solid plot device).

There’s something poignant in coming clean about the way we see the people we’ve shared long history with. The way that Margit acknowledges that she and Sigrid each believed something not-quite-true about the other:

“You always acted like I was so smart and had everything figured out, but I didn’t. I thought you did.”

It’s a hard discovery, realizing that no one really has it figured out. That figuring it out is the project.

All the while Margit is watching Sigrid sleep in the hospital, she’s trying to protect her parents by not telling them Sigrid almost died. She’s weathering the trauma and pain by herself. But also, she knows her parents wouldn’t be any help if they were there. She won’t tell her friends what’s happening. She’s falling apart, failing school—which is her anchor, what she believes she is good at—and finally a professor pulls her aside to ask if maybe she might not be doing alright.

It’s such a seemingly random lifeline that helps Margit eventually reach out for help from her friends, to reengage with her own life, to take ownership of her existence.

I get it. I sucked at asking for help my whole life. I spent high school drowning in depression and anxiety. I spiraled again in grad school. I had Sigrid’s penchant for acting out. But also Margit’s penchant for trying to act like I had my shit together while things spun wildly out of control.

I am a complete mix of these two people.

And then in my life—even when it was a flaming hot mess—there were moments of kismet and pure connection. Like when Margit helps rescue Isabelle—the upstairs neighbor she’s heard being threatened, being screamed at, and sobbing for weeks—from her abusive boyfriend. They try to wait him out in Margit’s apartment so Isabelle can go back and grab her stuff. But ultimately Margit, the girl who never wanted to inconvenience anyone, who wanted to fly under the radar whenever possible, reach out to Mo and her roommates for help. They pull off some mad-caper scenario in which Mo (Margit’s boyfriend) poses as a security guard and evacuates the building for a “bomb threat.” The abuser leaves and Isabelle walks away with her things. Safely. Because Margit was finally strong enough to reach outside herself, make waves, help someone else.

We all learn. Sometimes quickly. Sometimes slowly.

It took me years to understand that it was okay to take up space. Desirable even. That my feelings and my state of being wasn’t too much. That I was just enough as-is. But that there is always greater peace, more equilibrium, more acceptance to work toward. And that is okay, too.

Finally, finally, at the end of the book, we get to hear directly from Sigrid. Let’s just say my identification with Sigrid didn’t lessen after hearing straight from her. Especially on her relationship with her sister:

“She and I got into a fight because I lost my cool and threw pie guts at Mom. I watched Marg scold me, and realized she didn’t understand my perspective. She wanted to maintain peace, ignore our problems, and placate everyone. Her objective was to avoid conflict. Mine wasn’t. I wanted issues to be acknowledged. I wanted to address it when our family behaved badly. I was sick of playing along. I felt like I was a black sheep, and she was an enabler. I was the target of everyone’s frustration, and she kept the peace for everyone but me….I felt like I was falling down a well, and rather than offer a hand, Marit reprimanded me for screaming.”

Family dynamics are just devastating, aren't they? The people that swear they love us can be our greatest undoing, especially when their actions don’t line up with their words. The isolation and rage that Sigrid felt isn’t exactly foreign to me. I haven’t not felt this way.

Which made the ending even sweeter.

I will let someone else tackle the ending. But I will say, it’s hard to pull off an ending to a story like this that doesn’t feel trite. That honors both characters and the work they’ve done to discover who they really want to be—instead of playing their assigned family roles.

Maybe that’s what really got me about this novel: it is all about the journey toward understanding who you’ve been, who you want to be, and the work it will take to get there.

Life is beautiful. And hard. We Could Be Rats captured all that for me. It made me feel seen.

And that made me love it forever.

The End.

I get it. I too am profoundly, irrationally in love with We Could Be Rats. It’s hard to find what and where to begin my love letter to this book. I think I’ve narrowed it down to three thoughts I want to share…

1. Dear Emily Austin: This book will stay with me, forever. A main reason being it's composition. The format was one-of-a-kind and layered. It delivered heart-wrenching content in a way that did not leave me devastated, but hopeful. That ending was simultaneously poetic and real. I can only hope all people get the chance to heal relationships, truly work to understand each other, and communicate on one another's level as our sisters do. We all deserve to see pink skies. I will certainly re-read this book. I am eager to see how I interpret the letters now that I know the author is Margit. And that transitions us to...

2. Dear Margit: I am you. You are me. While I am an only child, I too had a parent with a very loud and aggressive and unreasonable swamp monster persona. I too walked on eggshells growing up. No one can tiptoe, or close a door, or cook themselves breakfast in a microwave as silently as I can. I deeply felt you, Margit. In every way. I was saved too by friends, therapists, and connections that did the brave and difficult thing of reaching out a helping hand to me. Margit, we can protect ourselves. We can take up all the space we need. We can build our own family and support system. And with that...

3. Dear Sigrid: I want dream as you do. You are what kept me hopeful in this book. How you fought to keep imagination and happiness alive. How your closing thoughts always delivered a positive outlook, against all odds. You taught me how without a connection even the most positive and bright soul can sputter. It inspires me to connect more. I am so glad your flame is getting fanned with a new relationship with your sister at the close of this book. We all can learn from Sigrid. Ultimately, she chose to imagine redemption and rebirth, not revenge, for a true villain like Kevin Fliner. Imagine a world where more people felt that way... I see pink skies when I do. I see a lot of fat and happy rats when I do.

The structure of the story did so much in building Sigrid’s character in my mind. When we finally learn that Margit has written those first letters, I had to stop myself so many times once the truth of it started to come to light. I had created a character in my head based off Margit’s perspective and it stuck. While so much of what Margit constructed was based on the real Sigrid, Margit’s perspective was inextricably woven in.

It is generally said that no one knows us like we know ourselves. And how we see ourselves is generally considered the “real” version. But this story proves just how much the perspective of those around you changes your life and changes how you think about yourself. Margit and Sigrid both struggle with what “real” means for them.

That was a struggle I could really relate to, especially when it comes to family. Strangers will always have their thoughts of me but that is a pain that I can often put aside. Well, sometimes. But family ties run deep and the concrete perspectives they often have create their own cage which I often find myself silently screaming against. Because if you scream out loud, you are being dramatic or selfish, as Sigrid was often told.

What this book didn’t do was tell me there is a happily ever after end point. Where life makes sense, we know who we are, and everyone understands our struggles and our hearts. But it did something so much more beautiful than that. The final lines of the book create such a stunning moment. A literal and figurative exhale. Those moments where maybe someone does see us, even just for a second. In that same moment, we see ourselves too, in the same way. A fleeting moment of connection and sense of self. The moment passes, but another one will come again. Truly one of the most stunning endings I have ever read.